No Sleep, ©2024 William L. Brown. The restless sleep of refugees and displaced persons.

Tomorrow marks two years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine! “Anniversary” is too nice a word for such a monstrous act. Let us remember those who died, those who had their futures brutally stolen, and those whose lives were cruelly upended.

Where were you two years ago? News media reported February 23, 2022 on rising tensions in Ukraine. There were Russian troops massed on the border. Two days earlier Russian legislature recognized as Donetsk and Luhansk, Ukrainian regions occupied by Russia in 2014 as Russian territories. The “frozen conflict” along that front line was getting hotter with an unusual number of rocket and artillery strikes.

The Russians staged an obvious provocation, a Russian-quisling official in newly annexed territory blew up his own car and claimed it was bombed by the Ukrainians. The United States issued warnings about such provocations, and about an imminent invasion, as they had been doing for weeks. Up until that time, their warnings seemed a bit overwrought to Ukrainians.

I’d relocated from Kyiv to Lviv for four weeks, giving into pressure from friends and family who were worried by the American warnings. See my Feb 12, 2022 article Ticked-Talk.

February 23, 2022 was frantic. I’d purchased a plane ticket to Budapest the night before. The flight was at 12:45 PM, February 23. I had to pack, get to the outskirts of Liviv to the nearest lab that could do a rapid COVID-test, get back to city center, find a copy shop to print out my boarding pass, take my old lap-top to a computer-repair shop to have it reset to factory settings,, then ship it to a friend in Dnipro, find the bar (yes, a bar!) in Lviv where I could get the printed result of my COVID-test, meet the Airbnb concierge to give her the key and explain that I was leaving early and I did not want a refund, but please make the apartment available to refugees that may come. She locked the door behind me and I went out to the cobblestone street to wait for the Lyft taxi.

A bit dramatic to say it, but yes, mine was probably the Last Flight Out of Lviv.

One of many computer-repair shops in Lviv that try to look like Apple Stores, though there are no official Apple Stores in Ukraine. Photo ©2022 William L. Brown

Two days after the full-scale invasion I was in a Budapest coffee-house with a few other ex-pats, all of us texting our “gots.” “Got” as in “I got a friend on a refugee bus stuck on the border,” or “I got a friend who’s trapped behind Russian lines.”

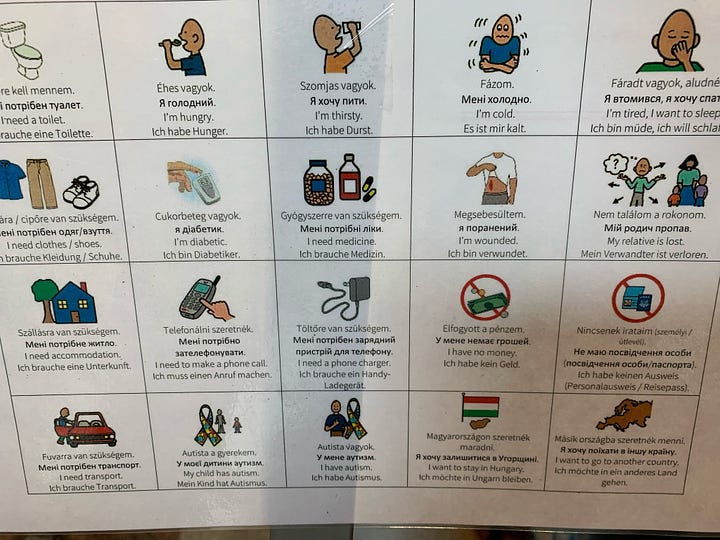

We frantically fielded questions and updates from friends, many of them running low on battery-power. We checked news and social media channels, passing information on to those who needed it. Then, we’d report to each other around the table, sharing info and resource links: border information such as which crossings were least slammed, which allowed crossings on foot.

Estimated waits for buses were days-long. Drivers had to decide whether to use fuel to stay warm at night, or conserve it to drive across the border. Military-age men were not allowed to leave the country, so many had to exit their cars and walk back, sometimes leaving a carful of family members with no driver.

I wrote about this at the time, pulling readers into their stories. I’m proud to say that many readers contributed money to them and to the local aid groups I wrote about.

So, where are they now? I will tell you in this and the next article, but I will not identify people by name to protect their privacy.

Two Years, © 2024 William L. Brown. The “terrible twos” for the Russians, we hope.

I’ve got a friend on a bus from Kyiv that’s been in line to cross the Polish border for two days and counting.

This friend, a young woman in her early 30s made it to Poland after three traumatizing days on a bus at the border. She fled Kyiv by train, despite the mass chaos at the Kyiv train station. The only order provided was was from soldiers stationed at the train doors who enforced the rule: women and children only. She wouldn’t have gotten in if her boyfriend hadn’t picked her up and thrown her into the carriage.

The train took her to Lviv, close to the border, where she found a bus to Poland. It pulled up near her, she asked “where is this bus going?” “Poland!” They said. She stepped on. A lucky break at the time, but the days-long wait on the border was not so lucky.

In Poland, she made a quick decision to keep going west. Poland was plainly overwhelmed with refugees, and Germany offered more benefits. Also, she spoke a little German, she’d taken a course.

In Germany she followed online refugee-chatter advice to bypass the big cities, which were overwhelmed. So she kept going south. In a small city near Stuttgart she found a host, an excellent host. She soon found work.

Her’s was the bright success story, or so I thought. I did not reckon on the effects of refugee trauma, German culture and human biology.

This gets personal, but it’s important to understand refugee life. A refugee’s usual problems don’t go away, they can become much worse.

This was an issue for her before she left Kyiv. She’s worried that her child-bearing years are ending soon. Ukrainian doctors consider pregnancies past the early 30s to be risky. So, time is short, she’s a refugee on her own, and she has no prospects for a suitable mate.

Months before the invasion, over coffee and tea at a Chinese restaurant in an ultra-modern Kyiv shopping mall, she told me her boyfriend did not want children. Should she stay with him or go? She loved him, which made it hard to walk away. Maybe he would change his mind? But what if he didn’t? She could not decide then. The war decided for her. They are no longer a couple.

The boyfriend still lives in Kyiv. He cannot leave the country even if he wanted to. He is worried about mobilization, as are most Ukrainian men. Some of them stay indoors as much as possible to avoid recruitment officers.

Out of Step, ©2022 William L. Brown. The refugee experience.

She found being single in Germany very difficult and lonely. Culturally, Germans are unfriendly to and often prejudiced against foreigners. Some American friends object to this characterization, saying America is just as bad or worse. I cite the internet bi-lingual comedian* Jordan Prince. Here’s his video about “how to make friends in Germany.” The answer is “You won’t.” Prince has over six-million views, and judging by the comments, he nails German culture1. So.

She was not able to make friends with any Germans outside the small circle of her host family. Her only option was other “foreigners.” She met a young man from Kazakhstan. He was, she said, more respectful of women than her former boyfriend. It turned out he was also more possessive, and violent. It ended badly. Now, she is traumatized, lonely, depressed, and unsure what to do.

This is how the Russian war on Ukraine affects not just the present, but the future. My friend may never have children if the war goes on for many years. There’s a strong possibility that it will be a long time. It effects the next generation, even.

Refugees are wearing out their welcome in some places. And they are worn out dealing with life in another culture and another language - their future in limbo.

I’ve got two friends, a mom and her 14-year-old son, in a train somewhere between Dnipro and Poland, a 900 km (560 mile) journey. Her phone battery is dying.

These friends also had a rough border crossing. Each four-person train compartment held a dozen people, and the corridors were packed. They also went to Germany. A distant relative with German connections helped them find a host in a small city in northern Germany. It was in a two bedroom-apartment. The host has one bedroom. The son has the other. The mom sleeps on a fold-down couch in the living room. She cooks, cleans and grocery-shops. The rest of the time she studies German and frets about her son and wonders if she’ll be able to find work, and if once she passes a language test that allows her to work, if she can find work in her field (micro-biology) or if she will have to work as a cleaner, as do many refugees.

The son was miserable. He missed his friends and home. He threw tantrums that his mom feared would get them kicked out of the apartment. She was also terribly homesick and worried that if she was away much longer she would lose her job back in Ukraine. So, they returned to Ukraine after a few months.

At that point the war was going well for Ukraine. The attack on Kyiv had been repelled, Kherson had been liberated and Russia routed from a big swath of occupied territory. But, in fall, 2022 came the air attacks - missiles and drones aimed at energy infrastructure and civilian targets. There were power outages most days, and the government urged those who could to leave the country to preserve power resources.

So my friends returned to the same German host last winter. This time the son was more enthusiastic to be back in Germany. Missiles exploding nearby, and daily five-hour electricity blackouts gave him a new perspective.

German Culture. Random tv screen-shot, Germany, 2023.

This time he liked his new school in Germany and told me he felt he had better prospects there. Since then, however, he was moved to a different school, much father and more difficult to get to. And, he’s not doing well in class.

This is another example of a problem refugees were dealing with before they were refugees. Back home before the invasion he was refusing to do homework and spending all his time in alone games. He’s returned to this lifestyle which gets him in trouble at school and also hampers his German language-learning. He’s interacting with Ukrainians online, not with German friends in the real world.

Since language and educational degrees are the keys to success in Germany, his future there no longer looks good. His mother is plagued by sleepless nights, not only about his future, but hers, and her parents’ back in Ukraine close to the front line. And then there are cultural/social anxieties.

Germans deserve credit for opening the immigration doors wide. I can’t imagine America waving millions of people over the border with a minimal screening process, saying “come across, we’ll sort you out later,” then providing free or subsidized housing and a stipend while the people are in language school.

That’s all great, but the Germans won’t let them WORK until they pass language tests. And that means living at poverty-level with constant worry about upcoming tests.

Another friend has a similar situation, but I’ll give you that story next time.

It’s very important to call your Congress-person and ask them to support Ukraine. Funding for Ukraine is held up by the Speaker of the House, who is playing domestic politics. I won’t go into the infuriating details. The important thing is that Ukraine armed forces are having munitions shortages due to the hold-up. This contributed, so we’re told, to the fall of Avdiivka last week.

So, please contact your representatives and ask them to bring the aid package to the floor and vote for it. Calling Congress is one of the most effective things a constituent can do. Politicians gauge voter-mood based on calls to their offices. Even more effective is to make a six-or-more figure donation to them. You can do that, too.

Please call your Congress-members.

Look up your representative at ziplook.house.gov.

Bi-lingual and cross-cultural comedy is a genre. For example, a young New Zealander, the Austrian Kiwi, who I ran into on the Munich main railway station platform, both of us en-route to the airport but stymied by an all-too-typical train cancellation, And here is Laura Ramoso who riffs on her German mother and Italian father.