Ecocide

Going deep

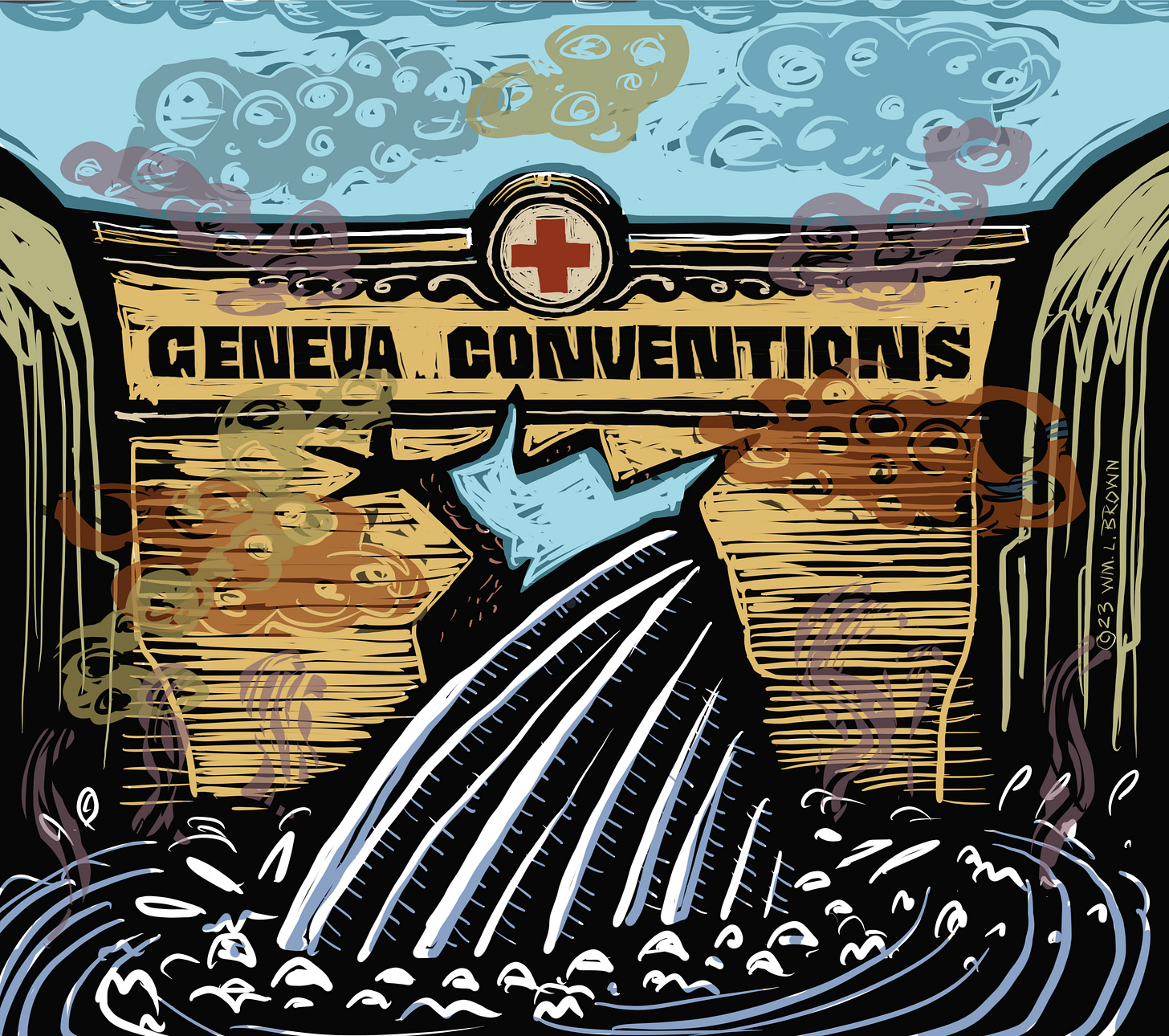

Kakhovka Dam, ©2023, William L. Brown.

This attack has been so shocking because it is an attack on the land itself, the very fabric of Ukraine. You hear the ugly word "ecocide" used, as previously there was no word to describe deliberate, indiscriminate, environmental destruction on the scale of a natural disaster.

Many of the victims live in little houses that they would have built and decorated over several years often with their own hands. Much of the furniture would have been handed down from parents and grandparents. Ukrainians don't buy home insurance. There will be no cheque to help start again. What is lost is gone forever.

These excerpts are from a piece written by “Drew” and sent to Ukraine: The Latest a podcast produced by the Telegraph. A large excerpt was featured on the June 27 episode. I requested a transcript. Francis Dearnley, the podcast’s Assistant Comment Editor kindly forwarded Drew’s full message. He said Drew gave permission to use it anywhere. It appears in full below.

Drew describes the effect of Russia’s intentional environmental disaster caused by blowing up the Kokhovka Dam, flooding villages and farms below with as much water contained in The Great Salt Lake mixed with oils, chemical toxins and explosives swept up in the current. It’s an attack on the heart of Ukrainian culture, says Drew, the heart being the village garden.

The flood covered 230 square miles, 68 percent of which was on the Russian-controlled side. According to the UN, the flood affected around 100,000 inhabitants directly.

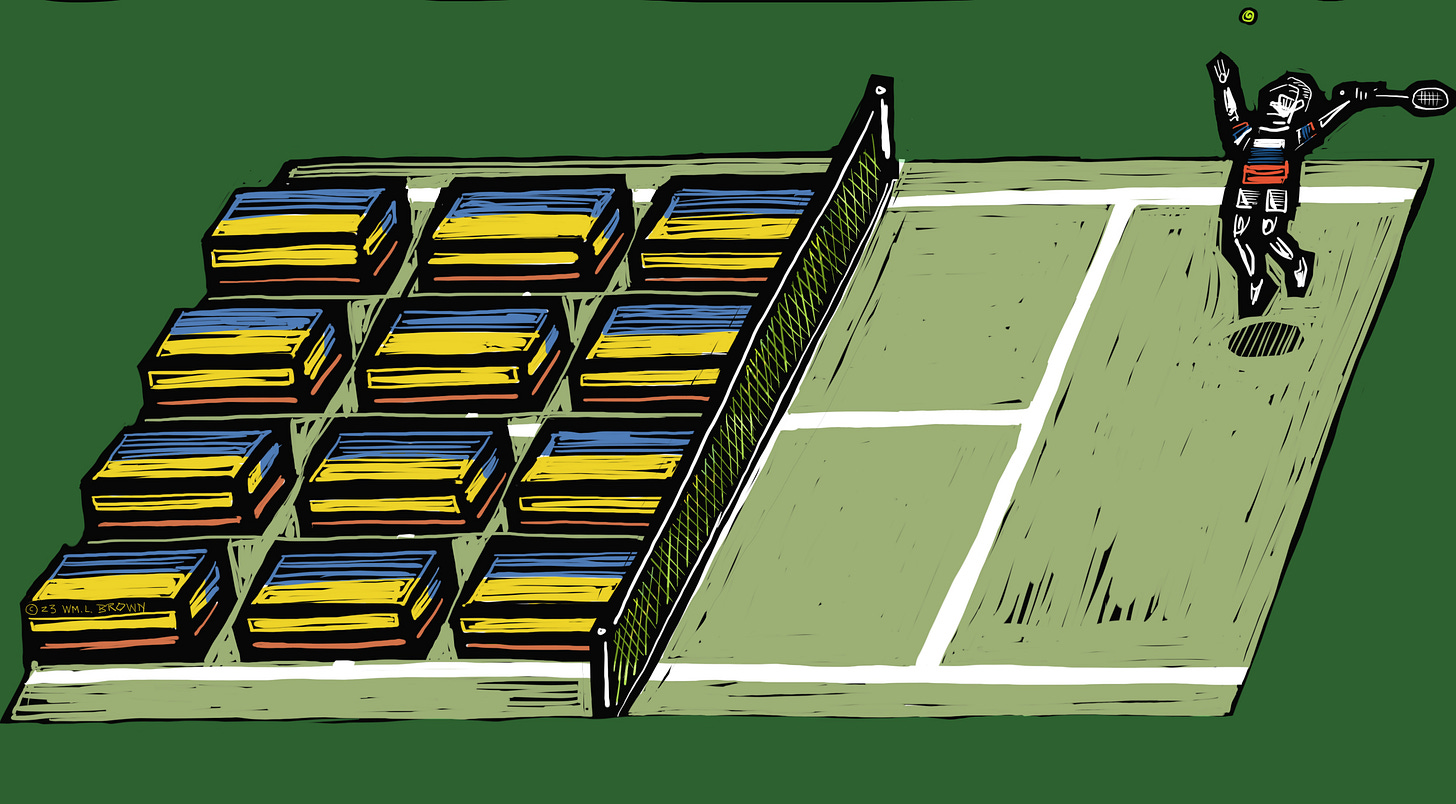

Ukraine’s path to NATO membership. ©2023, William L. Brown.

Drew was not the only one who criticized the international environmental community for its muted reaction to the disaster. Since then, environmental icon Greta Thunberg met Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky in Kyiv. They announced the formation of a working group on the environment which includes Thunberg, former Swedish Deputy Prime Minister Margot Wallström, European Parliament Vice President Heidi Hautala, and former Irish President Mary Robinson, as reported by AP.

The group, said Thunberg, will assess and monitor environmental damage inflicted by Russia on Ukraine and seek accountability.

Thunberg decried Russian atrocities. She said Russian forces “are deliberately targeting the environment and people’s livelihoods and homes. And therefore also destroying lives. Because this is, after all, a matter of people.” Video of her speech is here.

The June 27 Telegraph article, Ukraine’s toxic water crisis is escalating, by Samual Lovett describes the past and present issues in depth. The article was cited in the same Telegraph’s Ukraine: The Latest podcast as Drew’s piece.

This podcast has become my go-to source for daily war news. I highly recommend it.

Ukraine’s waters were already heavily compromised before the dam was broken. When I moved in Dnipro in 2019 I was warned, for example, of the annual summer algae bloom on the Dnipro River which makes swimming in it dangerous or unpleasant.

Radiation has long been a problem. The 1986 Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant disaster is well known. It contaminated the surrounding grounds and washed radioactive particles downstream where where sank into bottom sediments. The Kakhovka Dam flood may have stirred them up.

Not so well known is the Yunkum Mine in Donetsk. It was used for Soviet nuclear tests and sealed. But the Russian invasion of 2014 led to a control breakdown and the mine flooded. According to a study cited in the article, radiation is expected to leech out to rivers and reservoirs in another decade.

As Russians are welcomed back this year to the Wimbledon international tennis tournament, Ukraine reminds the world that over 260 Ukrainian athletes have died in Russia’s war. ©2023, William L. Brown

The article says there are two hundred and twenty other Ukrainian mines flooded due to power outages caused by Russian air attacks. These risk poisoning local groundwater with heavy metals and sulfates.

Attacks on industrial sites, oil depots, ammunition dumps and military positions have contaminated air and water with heavy metals and other toxins.

Many areas lost clean water due to power-outages and occupation. Millions have been effected, and though some water systems have been restored, the water is not as clean, and in some cases, is more corrosive to the water infrastructure.

The dam-busting flood swept with it industrial oils, fuel, heavy metals, toxins, chemical fertilizers from fields, industrial waste, 150 tons of machine oil from the dam, contaminated sediments, ammunition and explosive mines.

The article, says the catastrophic flooding swept across 230 square miles of land, causing “generational fallout:” ruined farmland, reduced crop harvests, bird and fish die-offs, and microclimate collapse. The area is part of or close to the battle zone, and some of it is in occupied territory, which makes aid difficult.

From “Drew:”

I think it's important to understand something about the culture of the people in the areas affected by Russia's attack on the dam at Nova Kakhovka and how the attack itself and the lack of an international response has been perceived in Ukraine.

Many of the victims live in little houses that they would have built and decorated over several years often with their own hands. Much of the furniture would have been handed down from parents and grandparents. Ukrainians don't buy home insurance. There will be no cheque to help start again. What is lost is gone forever.

Ukrainians don't trust banks either. They keep their savings in foreign currency and when they have enough, they buy property or land. Unlike people in the UK who waste their lives mowing lawns and trimming decorative bushes, Ukrainians pride themselves on using their land to grow food. The British garden is a tidy, sterile, soulless place. The Ukrainian garden is productive and alive. You won't see empty lawns and astroturfed front yards, instead, they grow potatoes, onions, carrots, courgettes, eggplants and beetroot. Their gardens also contain all kinds of berry bushes and fruit trees. Many keep chickens, rabbits, cows, and pigs. There'll be whole communities of babushkas whose lives revolve around their gardens, pets, and livestock. Gardening for them is not a hobby but a way of life. Downstream of the dam, all this is gone.

Ukraine is also one of the world's biggest honey producers. I may be biased but I reckon it's the best honey in the world. Every Ukrainian knows a beekeeper. You see beehives everywhere. I remember a friend's father who wouldn't leave home when the Russians attacked because he couldn't leave his bees. For me, one of the most poignant images of the attack is a photograph of a beehive, painted in the national colours, floating away in the floodwaters, with the bees clinging to the top.

Traditional Ukrainian beehives, National Museum of Ukrainian Architecture and Culture, Kyiv, Photo: ©2021, William L. Brown.

The Kherson region is most famous for its watermelons. In late summer the whole country seems to live on them. You'll see cages on street corners piled high with them wherever you go. You're supposed to tap them with your fingers to check the quality. I've never figured out what you should listen for so choose a random one, like an amateur.

Many Westerners labour under the delusion that the climate in Ukraine is cold and wet. This is ironic because Ukraine actually contains one of Europe's very few deserts, the Oleskiy Sands. It has a unique habitat, but it's downstream of the dam and is flooded now too.

When I tell older Ukrainians that I grew up in a British village they always ask the same three questions: How much land did you have? What did your parents grow? What animals did you keep? My answers baffle them: a small patch of grass, rhododendrons, we had a dog, and some tropical fish.

Growing up in the Soviet Union taught them to be reserved with strangers and suspicious of foreigners. The easiest way to break the ice is simply to ask about their garden back in "the village". Ukrainians generally aren't given to bragging, with one exception: their gardens. You'll be treated to a comprehensive, virtual guided tour. They'll tell you who planted what, where and when. Then they'll spend as long as you let them effusing over the incomparable quality of what they've grown.

Traditional Ukrainian village house, National Museum of Ukrainian Architecture and Culture, Kyiv. Photo: ©2021, William L. Brown.

A lot of Ukrainians were raised on stories from their grandparents of the famine in the thirties when the Soviets stole their harvest to feed Russia and sell to the West. Russia may have Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy, but in Ukraine you don't need to read a book the size of a brick to understand something about life. Just ask a babushka about her family history. They're amazing people. They've lived through so much: war, famine, occupation, floods the Nazis, the Soviets, Chornobyl and now Russia. Many of the houses now underwater will have contained storerooms or cellars with enough jars of pickles and jam to feed a small army "just in case". But all that sweat and toil has been for nothing.

The Soviets systematically mocked village life but it's central to Ukrainians' sense of identity. Younger Ukrainians often live in cities where they move from flat to flat. The village homes of their parents and grandparents are like an anchor for their entire extended families. They return for holidays, to help out with the garden and leave their kids there for the summer. There, children eat fresh fruit, breathe fresh air, hang out all day in the sunshine and go swimming in the river. It's also often where, prior to independence, many Ukrainians learned to speak their mother tongue. Historically, Russian was much more commonly spoken in the cities but Ukrainian was kept alive in the countryside.

I often joke with my Ukrainian friends that a zombie film set in Ukraine would be the most boring movie ever. In the "civilised world" when zombies attack, the survivors fight over tinned food, guns, and ammunition. Ukrainians would just head to their villages and sow, harvest, and pickle. They are survivors. If you know their history, they've had to be. In the last few years, the people of Kherson have endured COVID, war, occupation and now this: everything they own, all they've grown, harvested, and stored, gone in a few hours.

Traditional Ukrainian homemade liquors, National Museum of Ukrainian Architecture and Culture, Kyiv. Photo: ©2021, William L. Brown.

Before it was occupied by the Russian Empire, Ukraine was populated by Cossacks. Three things unite the Ukrainians of today with their Cossack ancestors: they are farmers, they are warriors and they are free. Growing your own food connects you to the land in a way that most Westerners don't understand. The Soviets tried to break this bond by confiscating everything, starving them and forcing them to work on collective farms. Millions died but they never broke Ukraine. When they were given a chance for freedom, they took it with 92.3% voting for independence in the 1991 referendum. A lot of Russians took this rejection personally, including their beloved, little Tsar.

The yellow and blue of the Ukrainian flag represent a wheat field and the sky. Their soil they call "black earth". The way they speak of it, you'd think it had supernatural power. They don't talk of Russian soldiers dying, but of "the earth covering them". Ukrainian heroes will be buried and mourned: Russians will "become fertiliser". Famously, in the very first days of the invasion, one Ukrainian babushka gave occupying Russians sunflower seeds to put in their pockets "to grow where their bodies fall".

Ukrainian , Dnipropetrovsk Oblast. Photo: ©2022, William L. Brown.

This attack has been so shocking because it is an attack on the land itself, the very fabric of Ukraine. You hear the ugly word "ecocide" used, as previously there was no word to describe deliberate, indiscriminate, environmental destruction on the scale of a natural disaster.

Ukrainians are extremely grateful for all the moral, financial, and military support they have received but the lack of empathy and action over this attack has caused much consternation. The silence of the green movement is shameful. You can bet they'll have plenty to say when the time comes and the money is found to rebuild Ukraine's battered energy infrastructure. But where are they now, in Ukraine's hour of need?"