Anxiety

Normalized

“Tse normalno” [Це нормално], meaning “It’s normal,” is a common Ukrainian response to “how are you?,” “what’s new?” or “how do you live with the daily sirens, air attacks, electricity blackouts, and water and heat outages?”

“It’s normal” is the brave, defiant response, but there’s “normal,” and then there’s “normalization.” People can normalize any situation as long they have basics: food, home, sleep, a toilet, enough heat and water to stay alive. Even it they don’t get enough of these essentials, they can feel - in the moment - as though it’s not so bad. A person can deal with this. It’s normal.

Around the block

But it’s not. If all was normal, I’d have written this months ago. Living only a few weeks in Ukraine last October and November had an effect - a writer’s block. I was never in any real danger, but apparently deep in my subconscious something got poked. Now a gang of feral brain cells have posted detour signs around the site, and won’t explain why. “Don’t go there! See, there’s something more interesting over yonder!”

I’d understand if I’d had one big moment of terror, but I didn’t, There were a few disturbing times, but nothing like what Ukrainians have gone through in a year of daily air-warnings, power, water, heat and internet outages, their lives and loved ones frequently in danger from missiles, rockets and drones. I only had a brief visit. I’m outing myself as a light-weight - not for the first time.

See my Instagram account. I’ve been posting “one year ago today” photos and drawings: last days in Kyiv and hasty trip to Lviv to wait “until things blow over.”

Mass-trauma has been widely observed. I see it discussed in main-stream and social-media. One of my students, who before last year had no problems juggling career, parenthood and a postgraduate course, finds it difficult to focus on his thesis which is due soon. A friend has given up looking for work. A refugee friend has sleepless nights.

You may remember Ekaterina Minokova, language teacher and community activist in Dnipro. She mentioned PTSD lately in her public online diary, a window into everday Ukrainian life and bravery. I highly recommend it.

“During my morning lesson I figured out that I have a kind of PTSD. At my student's side there was a loud sound of a plane. He even didn't notice it but I automatically bent to the table and looked up. It took seconds. This is a strange reaction because there were only our planes over Dnipro. Some people report that they are not comfortable with planes now, even having a phobia - something that I will have to check about myself. Today my body reacted before I had a chance to think about it. People who experience the war are weird. I wonder what other surprises my brain and body prepare for me. I was busy today but when I think about it I can hardly understand why everything took so long.”

And here is the eloquent Larisa Babij in her December 20, 2022 A Kind of Refugee article.

“Drinking coffee in Kyiv, my friend the physical therapist says we all have PTSD. I’ve never been a fan of diagnoses. This is both a gift and a fault.”

She writes about the effects she’s observed in herself and others of being exposed to various degrees of danger.

“This kind of physical knowledge changes you, even if you still remember how to act civilized. You might blend right in but nobody knows where you’ve been and even if you try to say it in words they understand they remain on that side of the wall and your excruciating job is to be a translator.

“One gets used to living in inconsistency, to not being able to depend on anything or anybody. I feel changes in temperature, tiredness, anger. Not much else .... I’m sure I’ll regain the ability to feel when it becomes relevant again.”

The United Nations Development Program identified the problem last August and set up an online program for Ukrainians suffering from PTSD.

“Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an anxiety condition caused by very stressful, frightening or distressing events, now commonplace in Ukraine. Early signs of PTSD can include strong emotional reactions, reliving painful memories, insomnia, detachment and anxiety.”

As early as March 11, less than a month since Russia’s attack, a Scientific American article by psychiatrist Arash Javanbakht says,

“As Ukrainian cities came under attack, civilians saw explosions and death firsthand and began experiencing immediate disruptions to basic resources like electricity, food and water, and problems with reliable communication with loved ones.

“Ukrainians are also experiencing agonizing feelings of injustice and unfairness as their hard-earned democracy and freedom are being unjustifiably threatened, leaving some feeling insufficiently supported by their allies.”

“....such difficult experiences can lead to severe consequences including PTSD, depression and anxiety. PTSD symptoms include terrifying and realistic flashbacks of war scenes, intrusive memories of the trauma, panic, inability to sleep and nightmares, as well as avoidance of anything that resembles the trauma.”

It real scary

I wonder what my trauma was/is. I don’t recall any big moment of terror, just several queasy ones – as you get riding with a reckless driver.

One of my students felt something like this mid-January after a missile hit an apartment building in Dnipro, killing 40. The student lives in distant Odesa, but this one was harder on her than other bombings.

I think it was because the apartment building was so typical, in the Soviet-era style found in every city and town. Every Ukrainian has lived in such a place, or has a relative living in one.

She texted:

“It just home where people live”

“it can be any city, any building”

“and you don’t know when it happen.”

“It real scary.”

Two incidents disturbed me like this. On October 18 an explosive “kamikaze” drone hit an historic apartment building in central Kyiv. It killed a young couple. The wife was pregnant. The photos of the explosion and the big hole it made in the building were sobering. Iranian drones may be cheap and slow, but they pack enough explosives to smash down the top three floors of a five-story brick apartment building. My apartment is on the fourth floor.

A couple weeks later, an attack hit a house in my district. It looked frighteningly like my house and my neighbors' houses - same tan-yellow bricks, same trees, same simple pipe fence around the yard. “It real scary,” is right!

My Kyiv apartment building and neighborhood, November, 2022.

After both these attacks I slept in my clothes for a few days,, the Holy Trinity (passport, wallet, cellphone) in my pockets. And I didn’t sleep well.

Before the October 18 attack, I’d adopted the sangfroid of my Kyivian friends, largely ignoring the warning sirens, only relocating to my foam pad in the hallway if I heard any explosions at night. I scorned the metro station bomb shelter - a ten-minute, dark and uneven walk distant.

The attack of the 18th was the second of a series of nation-wide, about-once-a-week missile and drone attacks that have continued since Oct. 10. In each attack Russia fired from 70 to over 100 missiles and drones, most of them at energy infrastructure. I heard them in the distance once. I described the drone-raid on Kyiv in a previous NativeCpeaker article.

I developed a new sleeping protocol. I placed a bug-out bag containing vital papers, my computer devices, and a little food and water by the door every night where I could find it by feel.

Instead of sleeping in my street-clothes, I set out clothing that was warm and easy to slip on. I only turned one of the two door locks so i could get out faster. It was not as secure, but then that would make it easer for rescuers coming in. This felt more normal than sleeping in my clothes or moving permanently to the foam pad in the drafty hallway, so sleep was a little more comforting.

Nightly setup: sleeping pad on an old quilt spread out in the hallway, clothes on the stool, and bug-out bag partially visible on the floor to the right. October, 2022.

Still, it was not fully restful. I’m sure I’m not the only one in Kyiv who went to bed early and jumpy because the sirens might sound in the wee hours, as they did several times. They wailed one or two times a day, at all hours.

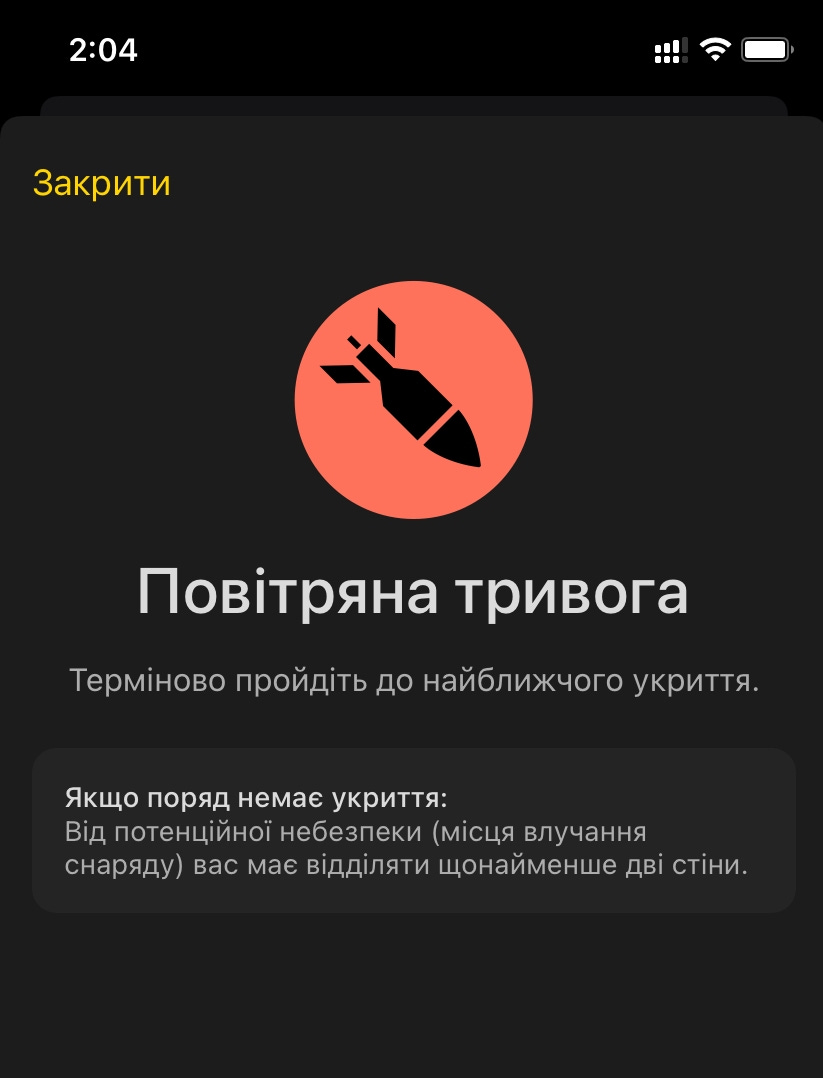

Screen grab from the Ukrainian Air Alert phone app. This alert was at 2:14 am, Oct. 16, 2022.

They do not have alarms in Ukraine, they have anxiety. The phrase повітряна тривога [povitryana tryvoha] translates as “air alarm” but the word we translate as “alarm” – “тривога” – literally means “anxiety.”

Anxiety is high this week in Ukraine. Rumormongers and even credible media and government sources say there may be a big missile attack this Friday, February 24th, the first anniversary of Russia’s offensive. It might be in tandem with a big military push in the Donbas region or Zaporizhia. There could be an attack where nobody expects. Maybe Putin has finally forced Lukashenko to commit Belarussian troops to the invasion.

There have been worrisome events. A Russian missile found almost intact has updated technology. Half of the thirty or so missiles Russia launched in a wave last week hit their targets. Usually only a handful of the 70-100 missiles in a typical weekly wave have gotten through. The Russians are changing their missile tactics, launching from river bed-level so they are hard to detect. What was the purpose of the Russian balloons dangling metal bits? Why are the Russians draining the river? Are the Ukrainians running out of ammunition? Maybe it’s the Russians who are running out of ammunition – or not? Where are the damn tanks? Why doesn’t the west send jet fighters?

On the other hand, look at the Russian tactics. They are sending their barely-trained soldiers into battle as targets, while what is left of the Russian professional army waits at the rear for the Ukrainians to use up all their ammo. As shockingly wasteful of human life as the tactic is, it may be wrking, but how long will the recruits remain ignorant, patriotic or compliant about their self-sacrifice?

How long before Russians start shooting at each other?

So many possibilities, rumors and facts. Not knowing which ones will actually come makes me anxious. How about you?

More anxiety upcoming in Part II.

Thanks, Woody! I struggled with how to write about this, since, as you indicate, I haven't been under the full force of the attack like folks in Ukraine are. In comparison mine seems like a minor complaint. I did it this way because I hoped my mild case would be relatable and show how even a small experience of war trauma can do damage. I also hope to break the writers block!

Holy shit, bill, this is felt across the miles n kilos. Hard to say "stay safe" to you without feeling like I'm excluding the folks really under the gun all the time. Victory and peace. Woody